- Home

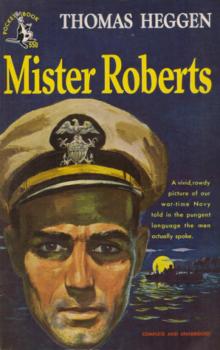

- Thomas Heggen

Mister Roberts

Mister Roberts Read online

Jerry eBooks

No copyright 2011 by Jerry eBooks

No rights reserved. All parts of this book may be reproduced in any form and by any means for any purpose without any prior written consent of anyone.

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

THE REAL “USS RELUCTANT”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

INTRODUCTION

Now, in the waning days of the second World War, this ship lies at anchor in the glassy bay of one of the back islands of the Pacific. It is a Navy cargo ship. You know it as a cargo ship by the five yawning hatches, by the house amidships, by the booms that bristle from the masts like mechanical arms. You know it as a Navy ship by the color (dark, dull blue), by the white numbers painted on the bow, and unfailingly by the thin ribbon of the commission pennant flying from the mainmast. In the Navy Register, this ship is listed as the Reluctant. Its crew never refer to it by name: to them it is always "this bucket."

In an approximate way it is possible to fix this ship in time. "The local civil time is 0614 and the day is one in the spring of 1945. Sunrise was three minutes ago and the officer-of-the-deck is not quite alert, for the red truck lights atop the masts are still burning. It is a breathless time, quiet and fresh and lovely. The water inside the bay is planed to perfect smoothness, and in the emergent light it is bronze-colored, and not yet blue. The sky, which will be an intense blue, is also dulled a little by the film of night. The inflamed sun floats an inch or so above the horizon, and the wine-red light it spreads does not hurt the eyes at all. Over on the island there begin to be signs of life. An arm of blue smoke climbs straight and clean from the palm groves. Down on the dock people are moving about. A jeep goes by on the beach road and leaves a puff of dust behind. But on this ship there seems to be no one stirring. Just off the bow, a school of flying fish breaks the water suddenly. In the quiet the effect is as startling as an explosion.

In Germany right now it would be seven o'clock at night. It would be quite dark, and perhaps there is a cold rain falling. In this darkness and in this rain the Allied armies are slogging on toward Berlin. Some stand as close as one hundred and fifty miles. Aachen and Cologne have fallen, inside of days Hanover will fall. Far around the girdle of the world, at Okinawa Gunto it is now three in the morning. Flares would be dripping their slow, wet light as the United States Tenth Army finishes its job. These are contemporary moments of that in which our ship lies stagnant in the bay.

Surely, then, since this is One World, the tranquil ship is only an appearance, this somnolence an illusion. Surely an artillery shell fired at Hanover ripples the air here. Surely a bomb dropped on Okinawa trembles these bulkheads. This is an American Man o' War, manned by American Fighting Men: who would know better than they that this is One World? Who indeed? Of course, then, this indolence is only seeming, this lethargy a facade: in actuality this ship must be throbbing with grim purposefulness, intense activity, and a high awareness of its destiny.

Of course.

Let us go aboard this Man o' War.

Step carefully there over little Red McLaughlin, sleeping on the hatch cover. Red is remarkable for being able to sleep anywhere: probably he was on his way down to the compartment when he dropped in his tracks, sound asleep. There do not, in truth, seem to be many people up yet—but then it is still a few minutes to reveille. Reveille is at six-thirty. In the Chiefs quarters there is one man up: it is Johnson, the chief master-at-arms. He is the one who makes reveille. Johnson is drinking coffee and he seems preoccupied: perhaps, as you suggest, his mind is thousands of miles away, following the battle-line in Germany. But no—to tell the truth—it is not. Johnson is thinking of a can of beer, and he is angry. Last night he hid the can carefully beneath a pile of dirty skivvies in his locker: now it is gone. Johnson is reasonably certain that Yarby, the chief yeoman, took it; but he cannot prove this. He is turning over in his mind ways of getting back at Yarby. Let us move on.

Down in the armory a group of six men sits tensely around a wooden box. You say they are discussing fortifications?—you distinctly heard the word "sandbag" spoken? Yes, you did: but it is feared that you heard it out of context. What Olson, the first-class gunner's mate, said was: "Now watch the son-of-a-bitch sandbag me!" Used like that, it is a common colloquialism of poker: this is an all-night poker game.

We find our way now to the crew's compartment. You are surprised to see so many men sleeping, and so soundly? Perhaps it would be revelatory to peer into their dreams. No doubt, as you say, we will find them haunted by battles fought and battles imminent. This man who snores so noisily is Stefanowski, machinist's mate second class. His dream? . . . well . . . there is a girl.. . she is inadequately clothed . .. she is smiling at Stefanowski ... let us not intrude.

You are doubtless right: certainly an officer will be more sensitive. In this stateroom, with his hand dangling over the side of the bunk, is Ensign Pulver. He is one of the engineering officers. And you are right; his dream is conditioned by the war. In his dream he is all alone in a lifeboat. He is lying there on a leather couch and there are cases of Schlitz beer stacked all about him. On the horizon he sees the ship go down at last; it goes down slowly, stern first. A swimming figure reaches the boat and clutches the gunwales. Without rising from his couch, Ensign Pulver takes the ball-bat at his side and smashes the man's hands. Every time the man gets his hands on the gunwales, Pulver pounds them with the bat. Finally the man sinks in a froth of bubbles. Who is this man—a Jap? No, it is the Captain. Ensign Pulver smiles happily and opens a can of beer.

What manner of ship is this? What does it do? What is its combat record? Well, those are fair questions, if difficult ones. The Reluctant, as was said, is a naval auxiliary. It operates in the back areas of the Pacific. In its holds it carries food and trucks and dungarees and toothpaste and toilet paper. For the most part it stays on its regular run, from Tedium to Apathy and back; about five days each way. It makes an occasional trip to Monotony, and once it made a run all the way to Ennui, a distance of two thousand nautical miles from Tedium. It performs its dreary and unthanked job, and performs it, if not inspiredly, then at least adequately.

It has shot down no enemy planes, nor has it fired upon any, nor has it seen any. It has sunk with its guns no enemy subs, but there was this once that it fired. This periscope, the lookout sighted it way off on the port beam, and the Captain, who was scared almost out of his mind, gave the order: "Commence firing!" The five-inch and the two port three-inch guns fired for perhaps ten minutes, and the showing was really rather embarrassing. The closest shell was three hundred yards off, and all the time the unimpressed periscope stayed right there. At one thousand yards it was identified as the protruding branch of a floating tree. The branch had a big bend in it and didn't even look much like a periscope.

So now you know: that is the kind of ship the Reluctant is. Admittedly it is not an heroic ship. Whether, though, you can also denounce its men as unheroic is another matter. Before that is summarily done, a few obvious facts about heroism should perhaps be pleaded; the first of them being that there are kinds of it. On this ship, for instance, you might want to consider Lieutenant Roberts as a hero. Lieutenant Roberts is a young man of sensitivity, perceptiveness, and idealism; attributes which are worthless and even inimical to such a community as this. He wants to be in the wa

r; he is powerfully drawn to the war and to the general desolation of the time, but he is held off, frustrated, defeated by the rather magnificently non-conductive character of his station. He is the high-strung instrument assuming the low-strung role. He has geared himself to the tempo of the ship and made the adjustment with—the words are not believed misplaced- gallantry, courage, and fortitude. Perhaps he is a kind of hero.

And then in simple justice to the undecorated men of the Reluctant it should also be pointed out that heroism —physical heroism—is very much a matter of opportunity. On the physical level heroism is not so much an act, implying volition, as it is a reflex. Apply the rubber hammer to the patella tendon and, commonly, you produce the knee jerk. Apply the situation permitting bravery to one hundred young males with actively functioning adrenal glands and, reasonably, you would produce seventy-five instances of clear-cut heroism. Would, that is, but for one thing: that after the fifty- first the word would dissolve into meaninglessness. Like the knee jerk, physical courage is perhaps latent and even implicit in the individual, needing only the application of situation, of opportunity, to reveal it. A case in point: Ensign Pulver.

Ensign Pulver is a healthy, highly normal young man who sleeps a great deal, is amiable, well-liked, and generally regarded by his shipmates as being rather worthless. At the instigation of forces well beyond his control, he joined the Naval Reserve and by the same forces was assigned to this ship, where he spends his time sleeping, discoursing, and plotting ingenious offensives against the Captain which he never executes. Alter the accidents, apply the situation, locate Pulver in the ball turret of a B-29 over Japan, and what do you have? You have Pulver, the Congressional Medal man, who single-handedly and successively shot down twenty-three attacking Zekes, fought the fire raging in his own ship, with his bare hands held together the severed wing struts and with his bare feet successfully landed the grievously wounded plane on its home field.

These, then—if the point is taken—are unheroic men only because they are non-combatant; whether unwillingly or merely unavoidably is not important. They fight no battles: ergo in a certain literal and narrow sense they are non-combatant. But in the larger vision these men are very definitely embattled, and rather curiously so. The enemy is not the unseen Jap, not the German, nor the abstract villainy of fascism: it is that credible and tangible villain, the Captain. The warfare is declared and continual, and the lines have long been drawn. On one side is the Captain, alone; opposing him are the other one hundred and seventy- eight members, officers and men, of the ship's company. It is quite an even match.

The Captain of a naval vessel is a curious affair. Personally he may be short, scrawny, unprepossessing; but a Captain is not a person and cannot be viewed as such. He is an embodiment. He is given stature, substance, and sometimes a new dimension by the massive, cumulative authority of' the Navy Department which looms behind him like a shadow. With some Captains this shadow is a great, terrifying cloud; with others, it is scarcely apparent at all: but with none can it go unnoticed. Now to this the necessary exception: Captain Morton. With Captain Morton it could and does up to a point go unnoticed. The crew knows instinctively that the Captain is vulnerable, that he is unaware of the full dimensions of his authority; and, thus stripped of his substance, they find him detestable and not at all terrifying. He is not hated, for in hate there is something of fear and something of respect, neither of which is present here. And you could not say loathed, for loathing is passive and this is an active feeling. Best say detested; vigorously disliked. As the chosen enemy he is the object of an incessant guerrilla warfare, which is, for the Navy, a most irregular business. Flat declarations like "Captain Morton is an old fart" appear in chalk from time to time on gun mounts; cigarette butts, an obsession of the Captain's, are mysteriously inserted into his cabin; his telephone rings at odd hours of the night; once when he was standing on the quarterdeck a helmet dropped from the flying bridge missed him by perhaps a yard—the margin of a warning. Childishness? Pettiness? Perhaps: but remember that these are the only weapons the men have. Remember that they are really hopelessly outmatched. Remember that the shadow, acknowledged or not, is there all the time.

Captain Morton is a tall bulging middle-aged man with a weak chin and a ragged mustache. He is bow- legged and broad-beamed (for which the crew would substitute "lard-assed"), and he walks with the absurd roll of an animated Popeye. If you ask, any crew member will give you the bill of particulars against the Captain, but he will be surprised that you find it necessary to ask. He will tell you that the man is stupid, incompetent, petty, vicious, treacherous. The signalmen or yeomen will insist that he is unable to understand the simplest message or letter. Anyone in the deck divisions will tell you that he is far more concerned with keeping the decks cleared of cigarette butts than with discharging cargo, his nominal mission. All of the crew will tell you of the petty persecution he directs against them: the preposterous insistence (for an auxiliary operating in the rear areas) that men topside wear hats and shirts at all times; the shouting and grumbling and name-calling; the stubborn refusal to permit recreation parties ashore; the absurd and constantly increasing prohibitions against leaning on the rail, sleeping on deck, gum-chewing, heavy-soled shoes, that and this and that. And you will be told with damning finality that the man is vulgar, foul- mouthed. In an indelicate community this charge may appear surprising, but of all it is clearly the most strongly laid.

These are the ostensible reasons for the feeling against the Captain; and possibly, possibly not, they are the real ones. It is for a student of causative psychology to determine whether the Captain created his own situation, or whether it was born, sired by boredom and dammed by apathy, of the need for such an obsessional pastime. The only thing abundantly certain is that it is there.

Now on this slumberous ship, this battle-ground, this bucket, there is sudden movement. Chief Johnson leans back in his chair, yawns, stretches, and gets up. He looks at his watch—0629—time to make reveille. He picks up his whistle, yawns again, and shuffles forward to the crew's compartment. Now there will be action on this torrid ship. Now the day will spring to life; now men will swarm the decks and the sounds of purposeful activity fill the air. Now at least, at reveille, this Man o' War will look the part.

Chief Johnson blows his whistle fiercely m the compartment. He starts forward and works aft among the bunks croaking in a raw, sing-song voice: "Reveille . .. Hit the deck! . . . Rise and shine! . . . Get out of them goddamn sacks! . . . What the hell you trying to do, sleep your life away? . .. Reveille . .. Hit the deck! . . ." He is like a raucous minstrel, the way he chants and wanders through the compartment. Here and there an eye cocks open and looks tolerantly upon the Chief; now and then a forgiving voice mumbles sleepily, "Okay chief okay . . ." but not a body moves, not a muscle stirs.

Chief Johnson reaches the after door. He turns around for a moment and surveys the sagging bunks. He has done his job: he has observed the rules. Some of these men, he knows, will get up in half an hour to eat breakfast. Most of the rest, the ones who don't eat breakfast, will probably get up at eight. Chief Johnson walks sleepily aft and turns in his own bunk to sleep until eight. Eight o'clock is a reasonable hour for a man's arising; and this is, above all else, a reasonable ship.

CHAPTER ONE

There were fourteen officers on the Reluctant and all of them were Reserves. Captain Morton was a lieutenant-commander, and on the outside had been in the merchant marine, where he claimed to hold a master's license. Mr. LeSueur, the executive officer, also a lieutenant-commander and also ex-merchant marine, swore that the Captain held only a first mate's license. Mr. LeSueur was a capable man who kept to himself and raged against the Captain with a fine singleness of purpose. The other officers represented the miscellany of pre-war America. Ensign Keith and Ensign Moulton had been college boys. Lieutenant (jg) Ed Pauley had been an insurance salesman. Lieutenant Carney had been a shoe clerk. Lieutenant (jg) Langston had been a school-teache

r. The new mantle of leadership fell uneasily upon these officers. Most of them, feeling ridiculous in it, renounced the role altogether and behaved as if they had no authority and no responsibility. Excepting Mr. LeSueur, excepting categorically the Captain, and excepting the Doctor as a special case, there was only one of these Reserves who successfully impersonated an officer, and he least of all was buying to. That was Lieutenant Roberts. He was a born leader; there is no other kind.

Lieutenant Roberts was the First Lieutenant of the Reluctant. The First Lieutenant of a ship is charged with its maintenance; he bosses the endless round of cleaning, scraping, painting, and repairing necessary to its upkeep. In itself the job is a considerable one and in this case the only real one on the ship, but Roberts had yet another job: cargo officer. That was one hell of a job. Roberts was out on deck all the time that the ship was working cargo, and whenever there was a special hurry about loading or discharging, he could figure on three days without sleep. And all the time he was standing deck watches, one in four, day in and out. He got very little sleep. He was a slender, blond boy of twenty-six and he had a shy, tilted smile. He was rather quiet, and his voice was soft and flat, but there was something in it that made people strain to listen. When he was angry he was very formidable, for without raising his voice he could achieve a savage, lashing sarcasm. He had been a medical student on the outside; he loathed the Captain; and all the circumstances of his present station were an agony to him. The crew worshiped him.

They really did. Devotion of a sort can be bought or commanded or bullied or begged, but it was accorded Roberts unanimously and voluntarily. He was the sort of leader who is followed blindly because he does not look back to see if he is being followed. For him the crew would turn out ten times the work that any other officer on the ship could command. He could not pass the galley without being offered a steak sandwich, or the bakery without a pie. At one time or another perhaps ninety per cent of the crew had asked him for advice. If it had been said of him once in the compartment it had been said a hundred times: "The best son- of-a-bitching officer in the goddamn Navy."

Mister Roberts

Mister Roberts